Species selection (step 1)#

As for any other project or analysis, the most important aspect is your scientific question. Why do you want to infer a phylogeny? What is the importance of the phylogeny to your study? How other studies will benefit from your phylogeny?

If you have recently sequenced some organisms and you simply want to have a rough idea of what taxonomic identity these sequences belong to, maybe a BLAST or a pair-wise comparison to reference databases (such as PR2 or SILVA) is more suited to your question.

Anyways, retrieving closely related sequences or proteins from public databases might be the first step towards the selection of the species that will be included in the phylogenetic tree. Here you are interested in integrating your group of interest in a broader evolutionary context, either within other groups or to explore the relationships within your group of interest. And to do so, you need a good representation of all known diversity.

Unfortunately, accessing all known diversity is not a straightforward task. Artefacts, such as chimeric sequences produced during amplification or errors during amplification or sequencing, might affect the quality and reliability of the molecular diversity. Therefore, and once again, depending on your scientific question you might tackle this step differently.

Let’s suppose that you have sequenced one organism that has never been sequenced and you want to know its phylogenetic patterns. A quick BLAST will let you know what broad group you are dealing with. Now comes the literature research: check previous phylogenetic analysis of the group of interest and try to retrieve similar sequences that have been previously used in other studies and complement with newly available sequences.

I normally prefer to start from a few and well established sequences of my group of interest and then remove and add more sequences in consecutive phylogenetic runs, depending on the given results and my question.

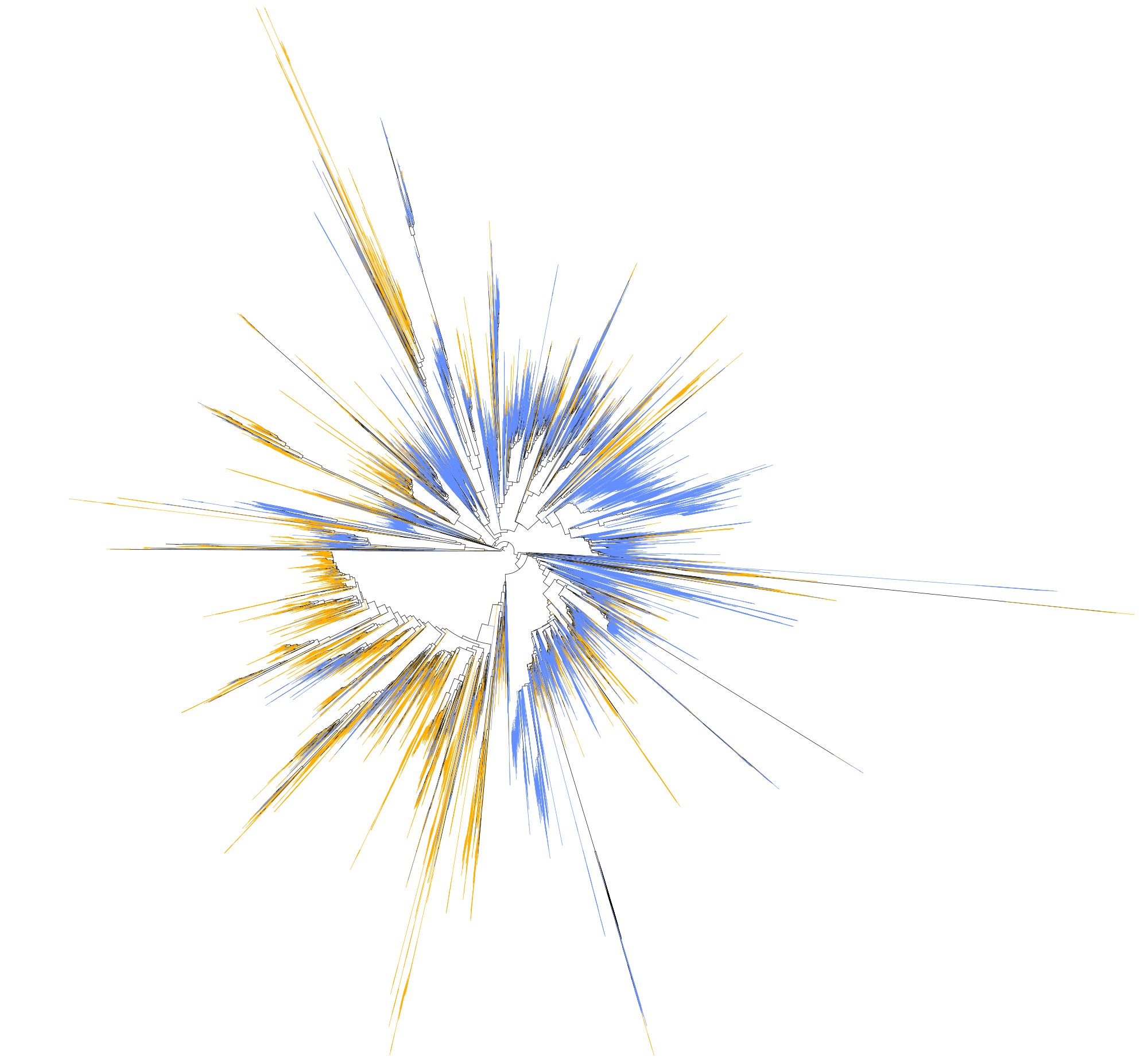

Closely related sequences will allow you accessing the phylogenetic relationships of your group of interest. Yet, to infer an evolutionary history and get a broader context of your group of interest it is needed to “order” the tree in an evolutionary sense: we need to root the tree.

When it comes to real data, the root of the tree should be the closest relatives of your group of interest (or outgroup) that are not your group of interest (or ingroup). For example if your group of interest are birds, then you might want to choose an outgroup within reptiles.

And if you are unsure of the quality or nature of your sequences, choosing more than one outgroup is very important to quickly spot artefacts or alignment problems.

Choosing a correct outgroup(s) is as important as choosing the correct species for your ingroup. However, many times it is simply not possible to choose, because of (for example) lack of resolved phylogenetic patterns, so you will have to make a decision among different options. For example if your group of interest is Rhizaria, you might want to include Stramenopiles, Alveolates and Telonemia as outgroups.